In the wake of the potato famine in Ireland in the mid 1840's, thousands of Irish-Catholic immigrants poured into the city of Philadelphia. Although looked at with suspicion by the native population, these immigrants met the needs of a rapidly growing city looking for a pool of ready labor.

Irishmen filled the manufacturing and construction jobs of an expanding industrial city. Irish women served as domestic servants, an occupation that was becoming an essential part of the lifestyle of the middle and upper classes.

Although life was not easy, many of these workers were able to save some money with the hope of purchasing a home or opening their own business. One problem facing these workers was the safekeeping of their hard earned pay. Many took advantage of the savings institutions which existed in the city at this time. Many others did not trust their savings with a private institution. Perhaps their unfamiliarity with a new environment or the anti-Catholic prejudice they encountered made them distrustful.

Bishop Francis P. Kenrick recognized the problem these workers faced. In May of 1848 he opened a bank to receive, and pay interest on, the deposits of working Catholics who did not want to use the private savings institutions. Popularly known as the "Bishop's Bank", it was managed by Mark Antony Frenaye, a Philadelphia Catholic businessman who served for many years as the financier and treasurer of the Diocese of Philadelphia.

The rules of the bank for conducting business are written in the front of the bank's first ledger book in Frenaye's own hand. They illustrate that the Diocese ran that bank according to sound business practices. Customer relations and secure investments were the guiding principles of the Bishop's bank.

According to Frenaye's rules office hours were to be posted on the door and adhered to punctually. Depositors were always to be treated politely. Impatience should never be shown. Payment should never be made in “uncurrent” money (a constant concern during this period) but should be in gold or city notes. Concerning disagreements over money owed he wrote, "With depositors never contend on small matters; if you cannot mildly convince them, pay; it is better to lose a few dollars, than to send abroad a discontented trumpet!"

Regarding investments Frenaye was adamant. The rules state, "Bear in mind that investments must always be made in stock of ready sale: City, or State of Pennsylvania. No other; City is the best. County stock is good, but of slow sale. Never purchase any other stock. Beware of Banks, Canals, railroads, other States of the Union, and all kinds of fancy stocks. Some of them may be good, but they are liable to ruinous fluctuations: Safety and quick sale, when needed, and not speculation, must always be the rule".

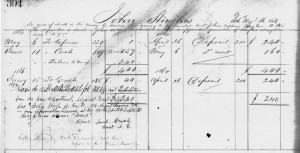

The story of the Bishop's Bank is not just the history of an institution but also of its individual depositors. The Philadelphia Archdiocesan Historical Research Center holds the ledgers and journals of the Bishop's bank. The ledger books contain the individual accounts for each depositor, and serve as a rich source of historical information.

In addition to account information, they include notations on the depositors. Most of these notations are brief and contain only age and place of origin or residence. Although the bank was intended to serve the needs of all Catholics in the diocese, the majority of depositors were Irish. This is evident from the large number of Irish surnames and the notations listing the various counties in Ireland as the place of origin.

Other notations are more lengthy. They might include personal information about the depositor or instructions on distributing money. They provide a brief but fascinating glimpse of the life of the depositor.

The notation for Johanna Reilly, who opened an account in 1852, reads "42 years old, St. Paul's Parish: a tall woman, pockmarked". This kind of description is not unusual at this time. If a person was illiterate and unable to write their name, a physical description or personal information was the only way to prove identification.

Other notations, though brief, offer insights into the personal life of the depositor. Mary Reynold's opened an account in 1848. Her notation reads, "wife of John Masterson. She does not want him to know of this deposit". John Strain also opened an account in 1848. His notation reads only "45 years in 1846". A later notation has been added which reads in bold letters, "he drinks, pay his wife only".

Some notations show how public events and private life overlap, sometimes with tragic results. John Hughes opened his account in April 1864. The first notation reads, "69th Reg. Pa. Vols. In case of death in the army he desires this money to be donated to St. John's Orphan Asylum, W. Phi." Written underneath is, "The depositor is dead. John McCue, his brother-in-law, is appointed guardian of Hughes daughter Ann-14 years".

Mark Frenaye managed the bank until September 23, 1857, when Bishop Wood, who had been a bank clerk before entering the priesthood, took over management. When a similar bank in Cincinnati failed, Archbishop Wood decided to liquidate the Bishop's Bank. However, confidence in the bank was so great that depositors refused to withdraw their money, even after Wood ordered that no interest be paid.

The bank continued in this way until Archbishop Ryan ordered that no more money be received. The bank lingered on until all deposits were returned. By the end of 1889 the Bishop's Bank no longer existed.